Overview

In Minnesota DNR’s Lewiston forestry administrative area, a common prescription for regeneration of mature oak stands includes underplanting oak seedlings before a regeneration timber harvest. We wanted to do an assessment of how well the practice had met oak regeneration objectives by gathering current data on several sites that had been underplanted with oak. This study is an assessment of oak regeneration and overall stand condition in 2021 (14 years after planting and harvest) for one of those sites.

Background on typical oak regeneration through pre-harvest underplanting prescription:

Seedlings have been planted prior to harvest (instead of after) because:

- They become established for a year or two, helping them be better able to grow and compete with other vegetation after exposure to full sunlight post-harvest.

- It is extremely difficult and expensive to plant seedlings after a harvest, with heavy amounts of slash on the ground.

- Non-oak species such as black walnut are mixed into plantings as appropriate for the site.

- Most often, the harvest prescription has been a clearcut with reserves, although there have also been some shelterwood harvests.

- Damage to underplanted seedlings during harvesting activity is usually modest. The young stems are pretty flexible and most often survive being run over by a skidder by bending but not breaking. Those that do break off generally resprout and exhibit the rapid juvenile growth associated with sprout origin stems.

- Crop tree release of desirable young regeneration, along with thinning of oak stump sprout clumps has typically been accomplished 8 to 15 years after the harvest.

Two interesting questions are raised by the study. We don’t have conclusive answers to either, so more case studies and research is needed for both:

1. Deer browse: Why is more oak regeneration growing past deer browse height on this site than on other, seemingly similar sites?

2. Vegetative competition: Why did more natural and underplanted oak regeneration survive and grow past early vegetative competition on this site than on other, seemingly similar sites?

Silviculture Objective(s)

1) Regenerate a mature oak stand to a young stand of similar composition.

2) Maintain and improve wildlife habitat with a strong component of oak trees in the new stand. Oak forests provide habitat for numerous wildlife species. The principal game species include white-tailed deer, turkey and gray squirrels, and in some areas ruffed grouse. Other important species include raccoon, opossum, red fox, bobcat, skunk, and a host of birds. One of oaks’ most important contributions to wildlife is mast, or acorns which are an important seasonal food source the animals listed above, and others. Source: North Central Manager’s Handbook for Oaks in the North Central States (GTR NC-37).

3) Improve timber quality and value. A good component of healthy, well-formed oaks and other fine hardwoods will help ensure high timber value at harvest time.

Pre-treatment stand description and condition

Stand establishment and management history:

Most of the mature oak stands in southeastern Minnesota at the time of project initiation in 2007 originated after control of regular fires after European settlement.

The stand was part of a privately owned farmstead until the state obtained it in 1979, so it probably had a history of use as a woodlot and wooded pasture prior to state ownership.

The site is steep to rolling, with several dry washes or coves. Aspect is mostly easterly to northeasterly. The lower portions of the slope are in a protected valley.

Pre-treatment species composition:

Table 1: 2006 Timber sale appraisal - individual tree selection black walnut harvest

Species Volume (Board Feet)

- Black Walnut 39,980

Table 2: 2007 Timber sale appraisal of volume of non-reserved merchantable trees with stems greater than 12 inches DBH

Species Volume (Board Feet)

- Red Oak 368,000

- White Oak 41,000

- Black Oak 25,000

- Basswood 22,500

- Central Hardwoods 20,500

- Elm 11,500

- Bur Oak 8,000

- Total: 496,500

Figure 1: 2006 black walnut selection harvest appraisal.

Figure 2: 2007 clearcut with reserves timber harvest appraisal.

Pre-treatment forest health issues:

None noted in timber appraisal.

Landowner objectives/situation:

While specific objectives vary from parcel to parcel, lands under the administration of DNR-Forestry are managed in alignment with Section Forest Resource Management Plans (SFRMP) to ensure that state forest management activities meet statewide goals for ecological protection, timber production, wildlife habitat and cultural/recreational values. The DNR assembles teams from the Divisions of Forestry, Fish & Wildlife, and Ecological & Water Resources who work with partners and the public to develop SFRMPs.

The Minnesota DNR goal for oak forest acreage at the time of project initiation was to maintain as much of it as possible through regeneration of mature stands.

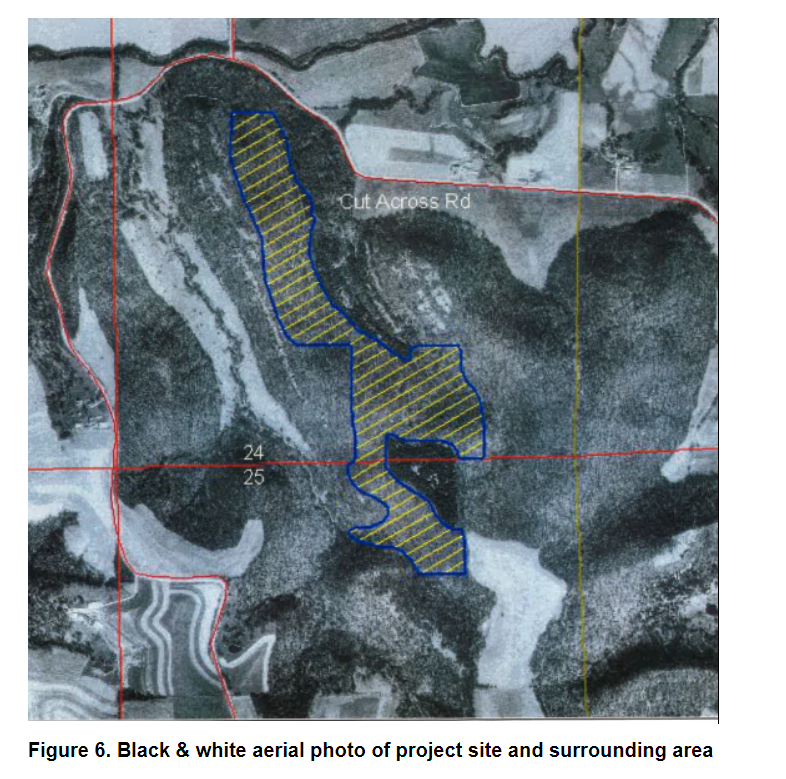

Figure 6: Black and white aerial photo of project site and surrounding area.

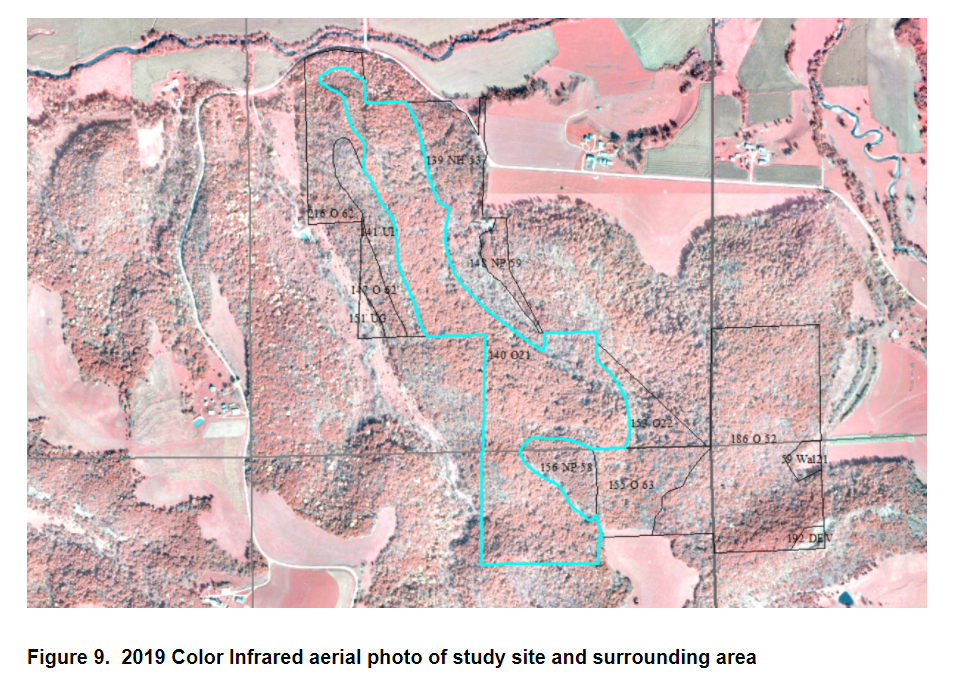

Figure 9: 2019 Color IR aerial photo of study site and surrounding area.

Silviculture Prescription

The following series of treatments were implemented:

|

Treatment |

Date |

Description |

Acres Treated |

|

Silvicultural assessment and timber sale appraisal |

2006 and 2007 |

Timber was appraised for sale, data was obtained on stems of existing regeneration, and the stand was assessed to determine a silvicultural strategy. |

NA |

|

Individual tree harvest of selected black walnut |

2006 |

Individual tree harvest of selected black walnut

|

95 |

| Underplanting |

Spring 2007 |

Bare root seedlings were hand underplanted prior to anticipated harvest at approximately 8’ x 7’ spacing. Target density was approximately 800 stems/ acre. No seedlings appear to have been planted in the biggest reserve patches. Records do not indicate whether the species mix was totally random across the site, or whether species were somewhat targeted for certain portions of the site. Species planted: Red Oak: 480 stems/acre, White Oak: 220 stems/acre, Black Walnut: 100 stems/acre |

81 |

|

Clearcut with reserves harvest |

2007 |

Trees greater than 12 inches DBH were harvested in a commercial clearcut with reserves harvest. Scattered trees and patches of larger bur, white, red and black oak and black walnut reserved for mast production as a seasonal wildlife food source, to provide den and roost trees, and as a seed source for regeneration. |

81 |

|

Post-sale killing of undesirable competing trees |

Fall, 2007 |

Stems of undesirable competing trees (boxelder, elm and ironwood) were killed by girdling with a chainsaw, and applying Tordon herbicide to the girdle wound. |

60 |

|

Crop tree release and oak sprout clump thinning |

March, 2017 |

Crop tree release: Release from competing woody vegetation up to 150 well-formed, desirable hardwood crop trees (3’ and taller) per acre. Crop trees were released using the following order of preference (from most preferred to least preferred): Walnut, Oak, Shagbark Hickory, Bitternut Hickory, healthy Butternut, Cherry, Hackberry, Sugar Maple, Silver Maple, Kentucky Coffeetree, Basswood, Cottonwood, Paper Birch and Aspen. Mast producing species take priority over non mast trees. Sprout thin: Mechanically cut stump sprout(s) of crop trees to the one best formed sprout near the base of the stump. |

78 |

|

Invasive species control |

March, 2017 |

Treat the following invasive exotics/non-desirable species with herbicide: all buckthorn, black locust, honey locust, multiflora rose, amur maple (ginnala) and non-native honeysuckles taller than 3’ tall, barberry taller than 2’, Oriental bittersweet and grape vines 1” diameter and larger. |

78 |

What actually happened during the treatment

Everything went according to plan with the harvests, planting, post-sale removal, and crop tree release. We have previously found that damage to underplanted seedlings during harvesting activity is usually modest, and found a similar outcome in this treatment.

Post-treatment assessment

The silvicultural prescription of pre-harvest underplanting, a clearcut with reserves harvest, and crop-tree release about 10 years after harvest has been successful at establishing desirable hardwood regeneration with a good oak component on this site.

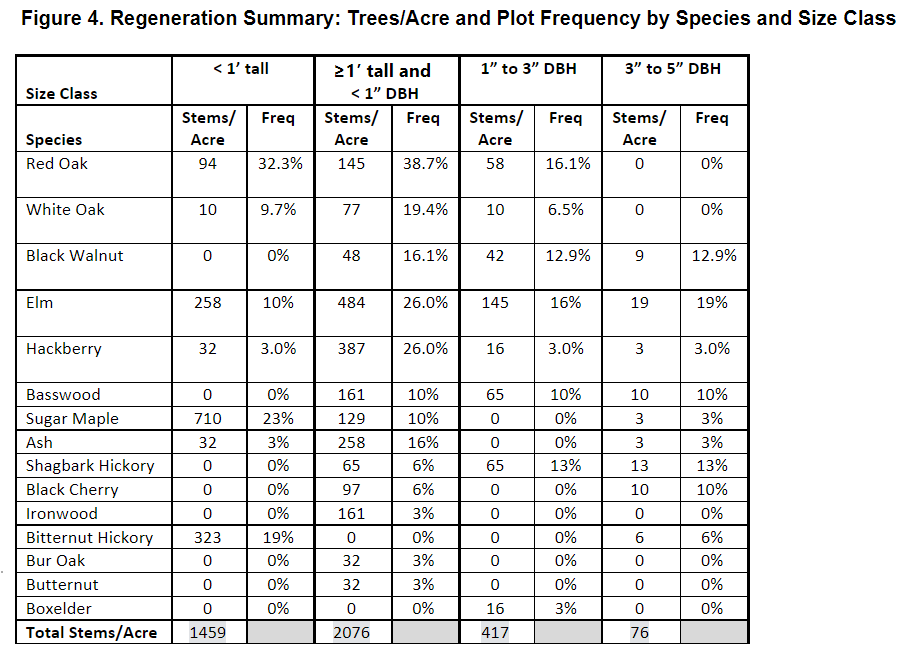

Figure 4: Regeneration summary: Trees per acre and plot frequency by species and size class.

Regeneration

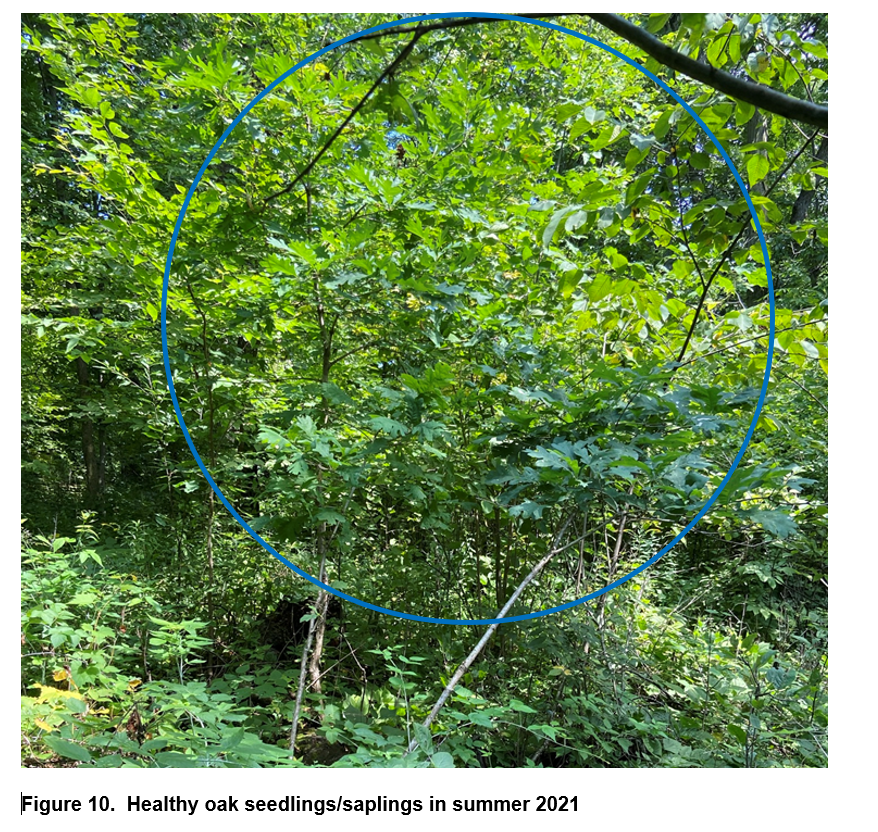

14 years after initial treatment, there is a mixture of desirable hardwood regeneration that is a good ecological fit for the site, including a good oak component (See Figure 4: Regeneration Summary). A fair number of these seedling and sapling oak stems are above deer browse, with some clearly at “free to grow” status. The origin of the oak regeneration is almost certainly a combination of planted and natural. It is difficult to conclusively tell the difference between planted and natural oak after 15 years, but there were places where we could ascertain a row pattern of the trees, indicating the planting origin of at least some of the oak regeneration.

Including all crop trees, the site appears to be meeting the MNDNR 15-year regeneration standard, which is: A minimum of 100 to 200 crop trees per acre with 75% of plots in “free-to-grow" condition.

In addition to the oak and walnut, there is a significant amount of other desirable hardwood species regeneration, including hackberry, basswood, shagbark hickory, black cherry, and (on some parts of the site) sugar maple.

Considering that at maturity, an average southeastern Minnesota oak stand has around 70 to 90 total trees per acre, this 14 year old stand is well on its way to reaching species composition objectives: a mixed hardwood stand with a good component of healthy oak, with high timber and wildlife value. Foresters will continue to monitor and assess the site over time. They should have good options to adjust species mix as desired through future crop tree release/thinning treatments.

The crop tree release work 10 years after harvest was critical for allowing oaks and other desirable shade-intolerant species to survive and thrive.

Two interesting questions are raised by the regeneration on this site, related to two of the biggest challenges to consistent oak regeneration: 1. deer browse, and 2. early vegetative competition.

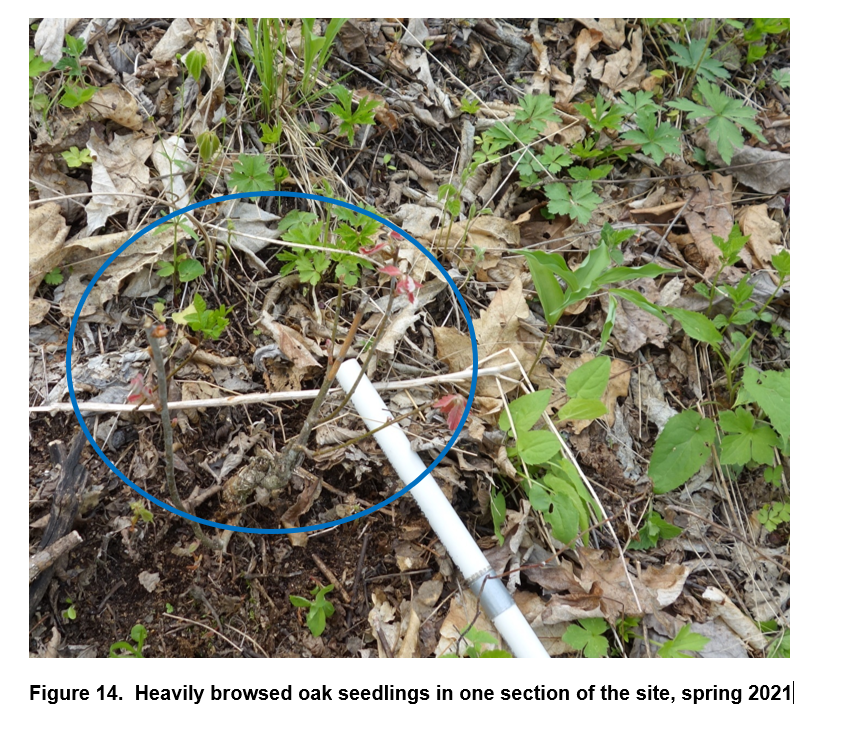

1. Deer browse: Why is more oak regeneration growing past deer browse height on this site than on a number of other, seemingly similar sites? There has clearly been significant deer browse damage on at least one section of this site (see Figure 14). However, on nearly half of the stand it appears that adequate numbers of oak seedlings and saplings are in the process of reaching heights where they are above deer browse level.

- Perhaps the relatively large size of the treatment area was a factor. In other words, the deer might have had enough area to meet their browse needs on only a portion of the site, and therefore spent less time feeding in other, less-favored portions of the site.

- It is also possible that deer hunting pressure is higher than on most other state land sites, resulting in lower deer populations than normal. From co-author, DNR Forester Jason Bland: “This unit has great public access and gets hunted hard during the deer season. I routinely see multiple vehicles parked at the access point during deer season. However, we should note that most DNR-administered state forest lands receive considerable hunting pressure. So, while this area is probably on the higher end of hunting pressure, it is also not completely unique in that regard."

- It is also possible that an exceptionally large amount of natural regeneration became established on this site right after the timber harvest. Unfortunately, we can’t know for sure because we do not have early regeneration check records for this site.

- Or, lower-than-normal deer predation might be related to all three factors postulated above, and/or other unknown factors.

One good research opportunity moving forward might be to obtain historical deer population data and try to assess oak regeneration results compared to local deer populations at treatment time.

2. Vegetative competition: Why did more underplanted and natural oak regeneration survive and grow past early vegetative competition on this site than on other, seemingly similar sites? Clearly, some of the initially established oak regeneration succumbed to shade from competing vegetation in the first few years after planting and harvest, before follow-up crop tree release work was done in year 10. However, on nearly half of the site adequate numbers of oak seedlings and saplings are in the process of reaching heights above competing vegetation.

- Part of the reason must have been good oak planting stock in 2007. MNDNR has struggled to obtain consistently good oak seedlings, with some years having very poor initial survival immediately after planting due to poor stock. However, there are plenty of sites that have been planted with good oak seedling stock where seedlings have been out-competed by heavy early vegetative competition, so that can’t be the entire answer here.

- It is also possible that an exceptionally large amount of natural regeneration became established on this site right after the timber harvest. Unfortunately, we can’t know for sure because we do not have early regeneration check records for this site.

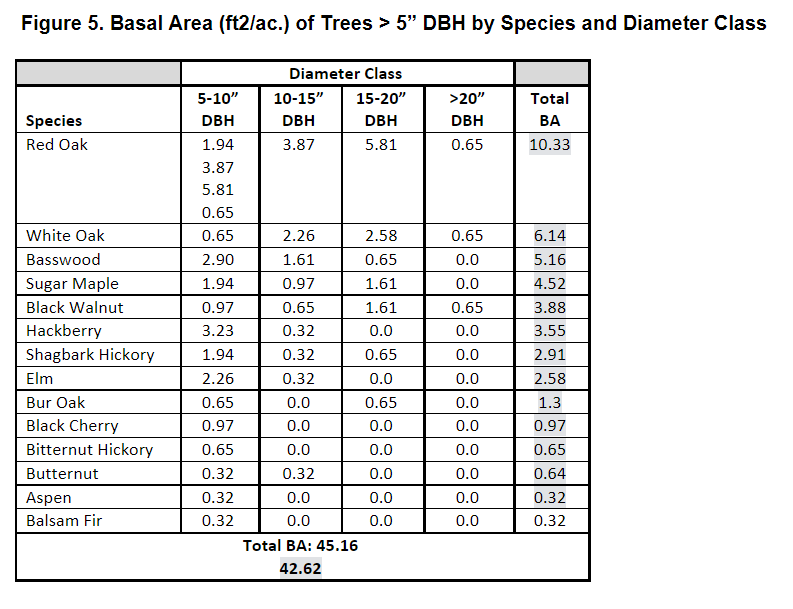

Residual overstory trees

We were most interested in regeneration for this study, so residual overstory trees are not a major part of the story here. However, we want to include data on residual overstory trees to give a full picture of site conditions. The data in Figure 5 shows basal area of residual tree stems in the study area.

Figure 5: Basal area (ft2/acre) of trees >5" DBH by species and diameter class.

Understory Plants

The understory plants we found on site were typical of the NPC. The understory layer was very dense and diverse which is a typical response of this vegetation layer post-harvest. Shrub species included gooseberry (Ribes missouriensis and R. cynosbati), raspberry and blackberry (Rubus spp.), chokecherry (Prunus virginia), and pagoda and grey dogwood (Cornus alternifolia and C. racemosa).

In terms of herbaceous plants, we found typical species that occur in MHs37 and a mix of species thought to be shade tolerant and intolerant, which is typical of young mesic hardwood stands. These species include: wild ginger (Asarum canadense), large flowered bellwort (Uvularia perfoliata), maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum), pointed leaved tick-trefoil (Desmodium glutinosum), bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), rue anemone (Thalictrum thalictroides), lopseed (Phryma leptostachya), zigzag goldenrod (Solidago flexicaulis), baneberry (Actea sp.), blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroidies), giant solomon’s seal (Polygonatum biflorum), white snakeroot (Ageratina altissima), black snakeroot (Sanicula spp.), hog peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata), mint species (Lamiaceae family), Bee balm (Monarda fistulosa), and goldenrods (Solidago spp.)

We found two plants worthy of special note:

- A state listed species of special concern.

- An overstory butternut that looked healthier than most, a state listed endangered species.

Invasive Species

Woody invasive species were treated with herbicide immediately after the timber sale, and also during the crop tree release treatment in year 10.

- Black locust: In spite of these control efforts, there is an increased presence of black locust coming into the stand from the adjacent locust stand.

- Buckthorn: There is currently little buckthorn on this site, although we did find it at low densities and frequency.

- Japanese barberry and garlic mustard: We found a few Japanese barberry in the stand and also some garlic mustard at low density and frequency.

Figure 10: Healthy oak seedlings/saplings in summer 2021

Figure 11: Healthy white oak sapling in summer 2021.

Figure 12: Fairly typical vegetation conditions in 2021.

Figure 13: Kevin O'Brien among regenerating mixed hardwood stems in the summer of 2021.

Figure 14: Heavily browsed oak seedlings in one section of the site in spring 2021.

Plans for future treatments

Monitor the stand through periodic inventory surveys. Harvest and regenerate the stand when it is chosen by the planning process. Control invasive species if necessary.

Foresters are considering another crop tree release due to the abundance of small oak present, but no decision has been made on this as of November 2022.

Costs and economic considerations

COSTS

Underplant seedlings: $26,740 (81 acres - 2007 dollars)

Post-sale TSI: $ 7,800 (60 acres- 2007 dollars)

Crop tree release: $16,635 (78 acres- 2017 dollars)

Total $ 632/ac. on 81 acres, 2007 and 2017 dollars

REVENUE

2006 black walnut harvest: $ 99,400 (2006 dollars)

2007 harvest: $179,500 (2007 dollars)

Total: $278,900, or $2,935/ac. on 95 acres, 2006 and 2007 dollars

Other notes

Crop tree release work was accomplished with special funding for habitat enhancement obtained from the Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Fund.

We had excellent review and editing help from MNDNR’s Silviculture Program Coordinator Mike Reinikainen.

This case study was developed with support from the United States Department of Agriculture's National Institute for Food and Agriculture, Renewable Resources Extension Act. Project #2021-46401-35956, principal investigator Eli Sagor, University of Minnesota.

Summary / lessons learned / additional thoughts

The silvicultural prescription of pre-harvest underplanting, a clearcut with reserves harvest, and crop-tree release about 10 years after harvest has been successful on this site.

14 years after initial treatment, there is a mixture of desirable hardwood regeneration that is a good ecological fit for the site, including a good oak component. A fair number of these seedling and sapling stems are above deer browse, with some clearly at “free to grow” status.

In addition to the oak and walnut, there is a significant amount of regeneration of other desirable hardwood species, including hackberry, basswood, shagbark hickory, black cherry, and (on some parts of the site) sugar maple.

This stand is well on its way to reaching species composition objectives: mixed hardwoods with a good component of oak, with high timber and wildlife value.

The crop tree release work 10 years after harvest was critical for allowing oaks and other desirable shade-intolerant species to survive and thrive. An earlier release may have been even better.

One “lesson learned” from MNDNR forester and co-author Jason Bland is that perhaps doing a regeneration check and crop tree release on this site earlier, within the first few years after harvest, would have resulted in even more oak regeneration survival.

We aren’t completely certain why more oak regeneration is growing past deer browse height on this site than on other, seemingly similar, sites

No browse protection practices were employed on the site, yet a significant amount of oak regeneration is in the process of reaching heights above deer browse levels.

Larger-than-average harvest area size and deer hunting pressure seem to be likely factors, but may not be the entire story. A third possibility is that the site may have had exceptionally good natural regeneration establishment after the timber harvest. We think a worthy subject for future research might be to obtain historical deer population data to see if anything related to oak regeneration success over the years could be learned from that.

We aren’t certain why the strategy of no vegetative competition control for the first 10 years after underplanting and harvest worked on this site, but has failed on other, seemingly similar sites

Good oak planting stock is a likely factor but there must be others, including the possibility that an exceptionally high amount of natural regeneration may have become established after the timber harvest. We will continue to seek answers to this question in future case studies.

More case studies and research on oak underplanting are needed

We asked ourselves what factors about this site caused the strategy of underplanting, harvesting, and crop tree release after 10 years to adequately meet oak regeneration objectives? What does it have in common with other successful sites, and what is different about sites where this silvicultural strategy (with no vegetative competition control or deer browse protection in the first 10 years) has not worked?

While we have postulated some possible causal factors in this study, we don’t have conclusive answers to these questions. We suggest that more case studies and research would be valuable.