Overview

The Cloquet Forestry Center is the primary research and education forest managed by the University of Minnesota. The ongoing objective of the Otter Creek burn unit is to produce high-quality red pine timber and work with fire to support the known and unknown timber and non-timber forest community members during the overstory rotation. The ecocultural fire restoration treatment has a short term goal of building community wellness, as evidenced through proliferation of fire-dependent (FD) understory plants, such as blueberry, sweetfern, and wintergreen, and a long-term goal of site preparation for pine regeneration at the end of this rotation.

Silviculture Objectives

The silvicultural objective was to support long-term canopy tree and community health and wellness through mid-rotation site preparation prescribed fire. This treatment supports non-tree community members and prepares the stand for next-generation red pine regeneration, estimated to be desired around 2070. Quantitatively, we sought to keep overstory tree mortality to less than 10%, to have the burn consume litter across at least 80-100%, and to top-kill at least 50% hazel and all other understory tree and shrub species. We desired to see an increase in the prevalence of known fire-loving understory species - such as blueberry, sweetfern, wintergreen, and bush honeysuckle - across the unit as an indicator that unknown fire-loving community members, such as soil fungi and microbiota, are being supported.

Pre-treatment stand description and condition

Figure 1: The Otter Creek unit during peak foliage on July 29, 2019, three years prior to implementing the prescribed burn treatment. Photo by Kyle Gill.

Stand establishment and management history

Establishment

The stand was established through pine plantings that followed three separate clearcut treatments of different portions of the stand.

- The southernmost three acres were clearcut in 1971 and hand planted with a mix of red pine and jack pine in 1974.

- An additional 12 acres were clearcut in 1975 with a mix of red pine, jack pine, and Scots pine planted in 1976.

- The remaining 29 acres were clearcut in 1982 and mechanically planted with red pine in 1983. Prior to this planting the slash was raked into piles using a skidder-mounted-root-rake and then burned.

Treatments prior to prescribed burning

- In 2011, the entire stand received a geometric first thinning treatment.

- Burn Unit preparation in 2020

- Fire breaks were created around three-quarters of the stand perimeter

- Lines of 6-10 feet in width were cut using a skid steer with a drum mulching attachment along the north, east, and south sides of the unit

- Pine Grove Road was the western fire break.

- Hazel and other brush was mechanically cut at ground height up to half a chain along the north, east, and south lines. Jack pine snags within one tree length of the fire breaks were also felled.

- Fire breaks were created around three-quarters of the stand perimeter

Pre-treatment species composition

At the time of the treatment, the total stand basal area was 86 square feet per acre which was almost entirely made up of red pine (72 square feet/acre) with an average DBH of 10.6 inches and a small amount of jack pine (8 square feet/acre) with an average DBH of 7.5 inches. Data for understory composition has yet to be summarized but is composed of a dense layer of 4-6 ft. tall beaked hazel across 70-75% of the stand, along with various grasses and other herbaceous species. Blueberry, sweetfern, wintergreen, and bush honeysuckle were present in relatively low densities. Following the 2011 thinning a few small pockets of 12-15 ft tall quaking aspen groves have sprung up.

Pre-treatment forest health issues

There are a variety of biophysical and social threats to the Otter Creek stand. Threats include, but are not limited to, mesophication, exclusion of indigenous people and indigenous ways of knowing and forest stewardship actions, armillaria root rot, Diploidia/Sirococcus shoot blights, Ips pine bark beetles, and red turpentine beetles. Structurally, a recalcitrant shrub layer of beaked hazelnut and “aspenification” - the potential unintended conversion of a community to an aspen monoculture - were and are threats. Noxious woody species have the potential to migrate into the unit due to the shared boundary with the CFC arboretum; these species include Siberian pea shrub, Siberian crab apple, and Tatarian maple. There is a potential economic threat to timber value merchantability due to char on wood or bark. Additional threats specific to burning that were considered included overstory crown scorch and mortality, bark beetles, and any other potential causes of crop tree mortality.

Landowner objectives/situation

The forest-wide objectives of the University of Minnesota Cloquet Forestry Center are to provide hands-on educational opportunities, to initiate and support new and ongoing research, to demonstrate novel and conventional forest stewardship practices for outreach, to maintain or increase the diversity of cover types, and age classes within the reasonable framework of the Ecological Classification System, to provide diverse habitat options for various wildlife species, to promote water and soil quality, and to document and protect areas of historical and cultural significance.

The stand-specific objectives are to support the known and unknown timber and non-timber forest community members during the overstory rotation and to prepare the stand for pine regeneration at the end of this rotation through the use of prescribed fire. An additional objective is to develop and demonstrate a prescription for restoring prescribed fire in a pine timber production stand or to consider ecological, economic, cultural, and social factors of including fire into a stewardship portfolio.

Silviculture prescription

Figure 2: A prescribed fire steward ignites understory fuels along the northwest burn unit perimeter. Photo by Kyle Gill, May 17, 2022.

This is a red pine cover-typed FDn33 ecological community with a short and long-term primary goal of pine timber production. Surface fire is being restored to support ecological community integrity and resilience, as a fire-dependent forest community member that has a short-duration and a long impact on structure and composition, and as a mid-rotation site preparation for the next generation of pine. The primary economic risk taken into account was the potential for bark char to reduce the merchantability of the timber. To mitigate this risk, we timed the prescribed fire(s) for at least 7-10 years prior to the next thinning treatment. The treatment is happening ten years following the prior thinning. Ideally, this would have happened 2-3 years following thinning, if sufficient fuel is available, or have been the second of two between-thinning fire treatments.

Figure 3: Fire works its way through the Otter Creek unit on May 17, 2022. Photo by Kyle Gill.

What happened during the treatment

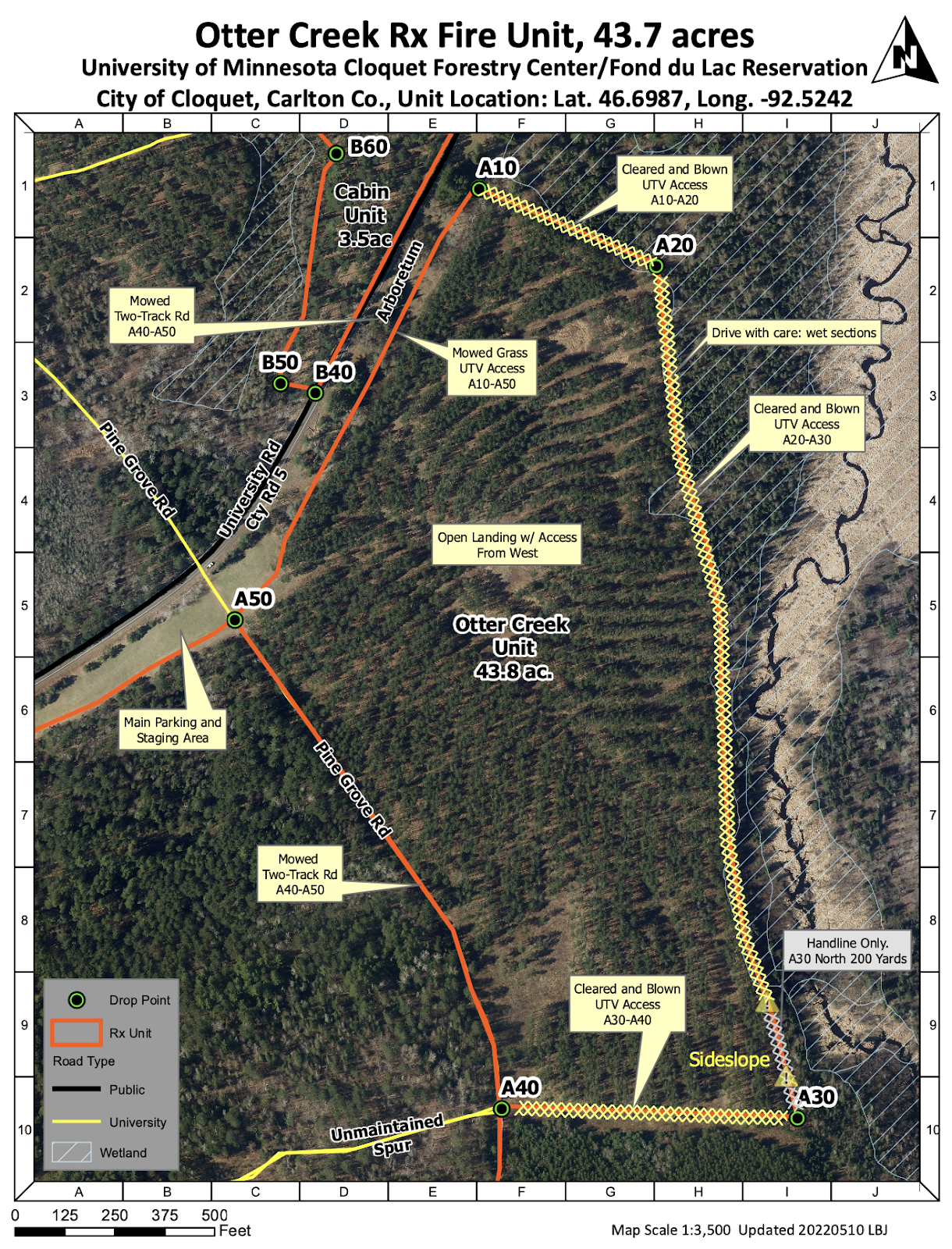

The prescribed burn was ignited in the early afternoon of May 17, 2022. We had light winds from the east so we generally worked from west to east into the wind. A test fire was ignited on the westernmost portion of the unit (point A50, see Figure 7). Black line was created along the northwest (A50-A10) and southwest (A50-A40) containment lines using two groups of walking igniters and a mix of backing fire and flanking strips spaced a half chain apart. Once sufficient black had been built on the western portion (A10 - A40) interior ignitions were conducted by two groups using a combination of strip head-fires and long flanking strips oriented west-east across the full length of the unit and spaced a half chain apart. Individual point ignition was used approximately 3 feet upwind of selected trees in heavier fuels to produce lower fire intensity and prevent bole scorch mortality. Ignition sequence was timed to allow the fire intensity to diminish from one strip before subsequent strips were ignited. Backing and flanking flame lengths were generally under a height of 2ft. Flame lengths sometimes exceeded 2ft where fire flanks converged. Fire rate of spread was approximately 5 chains per hour. Individual tree torching was observed in one tightly clustered pocket of jack pine within the unit interior. Holding crews monitored perimeters during and after ignitions; a few heavy fuels that were more than a chain from the perimeter were monitored for a few days following ignitions. Day-of equipment and personnel included 18 individuals, 2 UTVs with pumps, an additional UTV as an equipment mule, 1 type 6 engine, and an additional contingency type 6 engine. This exceeded the minimums required by our prescribed burn plan (see Godwin et al. 2020)

Post-treatment assessment

Post-treatment assessment has been primarily anecdotal at this point. Red pine mortality has been estimated at 0%. Percent top-kill of hardwood species, generally, and hazel, specifically, were estimated to be approximately 90% top kill; resprouting commenced within a few weeks of burning. Sprouts for many of the desired species (blueberry, etc.) have begun growing within the unit.

Figure 4: The Otter Creek unit on May 18, 2022, one day after conducting the prescribed burn showing the immediate post-burn conditions. Understory balsam fir that did not torch up and die immediately, like the one in the right foreground, were dead by the end of the growing season. Photo by Kyle Gill.

Costs and economic considerations

We found that attempting to isolate the specific costs per acre or unit to be incredibly difficult because there were direct costs (e.g. time of personnel and equipment during site preparation and implementation), indirect costs (e.g. plan preparation and equipment acquisition for other burns), and prior costs that could not be included (e.g. canopy-thinning timber sales from decades ago). Generally, larger burns cost less per acre to implement. Rough cost estimates included below consist of various cost components for the preparation and burning – in moderate fire weather conditions - of four of seven units included in the programmatic burn plan (Godwin et al. 2020: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/216903).

We opted for a programmatic/multi-unit burn plan because much of the detail included in the standard plan elements, such as notifications lists and sensitive smoke receptors and smoke management, are the same across our entire landbase. We contracted the writing of a programmatic burn plan with a certified burn boss through the Forest Stewards Guild. The total cost of plan preparation was $7,360. The plan was written for a total of seven units and 180 acres. The four units burned in 2022 totaled around 76 acres; Otter Creek (44 ac) was the largest of the four units.

Burn unit site preparation for all four units burned during spring 2022 was estimated at $10,000. Unit preparation for most units included burn unit perimeter construction, felling snags and ladder fuels within a chain of the perimeter, and ladder fuel reduction inside units. The burn bosses we worked with commented that the units were very well prepared and widened the weather windows (still within burn plan specifications) under which they were comfortable commencing ignitions; in other words, preparation efforts and likelihood of burning are directly correlated. The 2011 thinning in the Otter Creek unit ensured that the canopy trees had sufficient venting space and ladder fuels were not an issue. However, the $26,396 income from this commercial thinning went into the general CFC forest stewardship account and is not explicitly included in burn unit preparation financials.

The day-of costs for burning Otter Creek (44 ac) and Camp 8 (22 ac) units were around $33,367.00. This included three type 6 engines at $3089 each, and a short squad of 6 individuals at $4100 for a cost of $491/acre.

Costs were shared between multiple funders including the Cloquet Forestry Center Forest Management and Research group (CFC), Forest Stewards Guild, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and The Nature Conservancy (The Nature Conservancy). Funding for burn unit preparation was obtained through the MN Department of Natural Resources Conservation Partners Legacy (CPL) Program with in-kind funding from CFC. Funding for prescribed fire implementation came from the Bureau of Indian Affairs Fuels program and funding to the Fond du Lac Band through the Reserve Treaty Rights Lands (RTRL) Program with in-kind funding from CFC and TNC. Collaboration with local tribes and/or NGOs can create opportunities for increased funding and capacity. Costs of prescribed fire preparation and implementation can be reduced by using harvest prescriptions and timber sale contracts to prepare sites for prescribed fire. Also, the use of existing seasonal fire breaks (e.g. ag fields, Iowland forest, mesic forest) and infrastructure (roads, trails, lawns) can significantly reduce costs of unit preparation including labor and adverse impacts to the site.

Climate adaptations considerations

Climate adaptation was not a primary consideration in our hierarchy of objectives for burning in the Otter Creek stand. However, both thinning and prescribed fire are considered positive treatments for climate adaptation and resilience. Both fire and thinning support increased resistance and resilience to future known and unknown pressures through maintaining and enhancing community health and wellness. For example, the stand’s resistance to high-severity canopy fire was increased. And if a low-likelihood canopy fire does occur, we believe the stand has resilience; in other words, the community members or their descendants are well-placed for responding positively to such a disturbance.

Plans for future treatments

We would like to conduct a summer burn in 2024. Following this, the site will be allowed to rest until a merchantable thinning can be implemented, likely in 2030-2034. The proposed series of stewardship actions until a full regeneration harvest is to thin, conduct two to three burns within 5 years following thinning, let the stand rest for 7-10 years before the next thinning; or more simply: thin, burn, burn, rest, repeat.

Figure 5: The Otter Creek unit on October 6, 2022, roughly four months following the fire. Understory plants like large-leaved aster and raspberry - visible in this photo - bracken fern, and hazel responded well during the growing season. Photo by Kyle Gill.

Figure 6: Pyrophilic species, such as blueberries (red-leaved here) and sweetfern (green-leaved, middle right) started to show themselves by the end of the growing season. Photo by Kyle Gill.

Other notes

This treatment was developed with the support of Rachael Olesiak at the Cloquet Forestry Center; Scott Posner, the prescribed burn boss contracted through the Bureau of Indian Affairs; and Gezhiibideg Panek and Paul Priestley with the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Summary of lessons learned and closing thoughts

Summary of lessons learned

Working with forest fire takes a collaborative mindset and diverse group of people. As foresters, we need to learn to rely on the expertise and skill that is held within the wildland fire community - they have planning, practice, and monitoring skills that often are not taught or supported within the forestry community. We are grateful to have worked with a wide range of human partners to conduct this prescription. Otter Creek burn unit preparation was conducted in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy and Forest Stewards Guild with funding from The Nature Conservancy and the Conservation Partners Legacy Grant Program administered by the MN DNR. Contract planning and unit preparation was conducted by Forest Stewards Guild, Red Rock Fire, and TNT Timber. Prescribed burning was conducted in collaboration with the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and Bureau of Indian Affairs through an agreement with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and funding from the Reserved Treaty Rights Lands (RTRL) program. Tribal fire resources from Grand Portage, Leech Lake, Bois Forte, and Mille Lacs Bands provided assistance as well as fire staff with The Nature Conservancy. Scott Posner served as burn boss for implementation.

We have learned that the forestry community in Minnesota has built systemic limitations to conducting prescribed burns and that we could benefit by shifting our funding and work priorities from being suppression-response focused to engaging with more preventative actions. Simply put, it is difficult to get meaningful fire on the ground. The burn windows - the combination of biotic and abiotic conditions for burning - are small in Minnesota; the present risk-averse relationship with fire and anti-fire legal system further diminishes the windows. We maintain a lot of fear of fire socially in Minnesota and within the forestry community. We have become so fearful of the minor risks of wildfires that we have built our funding and personnel structures to prevent and limit forest fires. We propose that we shift our thinking and practices in two ways. One is to make sure to consider what we might lose from our xeric, fire-dependent forest communities if we are not willing to work with forest fires. We would consider it asinine to manage a wetland community by removing water and expecting the same suite of community members to thrive; it may be just as asinine to manage fire-dependent forests without fire and expect the full suite of species to thrive. A second is to respond by shifting our funding/personnel structures to be more supportive of routine preventative work, such as working with prescribing forest stand improvement fires. These are not minor shifts because the weight in the system is presently dedicated to fire prevention. However, we believe it is in the best interest of both our human and forest communities to develop a proactive and positive relationship with fire. Fire will be a part of these communities so let’s think about how to work with fire rather than continue to work against it.

Land recognition and appreciation

We would like to acknowledge and offer gratitude to the Land on which this work was conducted. Since 1909, the University of Minnesota Cloquet Forestry Center has been located on the lands of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa that were unceded/reserved during the signing of the 1854 Treaty of LaPointe. The unceded land was later broken apart due to the Nelson Act of 1889 to be made available to white settlement and colonial concepts of ownership and improvement. As part of this perceived improvement, the presence of ishkode (fire) was suppressed primarily by excluding Fond du Lac people as ignitors. Working with ishkode on the CFC grounds in collaboration with the FDL Natural Resources group is an act of acknowledging this history and an act of rebuilding trust between the University of Minnesota and Fond du Lac people.

Figure 7: The Otter Creek tactical burn unit map. Named location points A10-A50 were used for communications between wildland fire personnel during ignitions and holding operations. Map created by Lane Johnson.

Submitted by

Caleb Dunnewind

Kyle Gill

Kyle has been the CFC forest manager and research coordinator since 2015. He enjoys exploring stand development, silviculture, and the inherent biases that we bring to decision making. He feels it is important to see himself and other humans as community members of forested and non-forested ecological communities.

Lane Johnson

Lane aims to reconnect people to the benefits of wildland fire through fire-focused research, education, management, and policy. Lane is certified as a Fire Ecologist by the Association for Fire Ecology and is active with the Minnesota Prescribed Fire Council. He has been with the Cloquet Forestry Center since 2017.